International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trials or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946, to try the leaders of the Empire of Japan for "Class A" crimes, which were reserved for those who participated in a joint conspiracy to start and wage war.[1]

Twenty-eight Japanese military and political leaders were charged with waging aggressive war and with responsibility for conventional war crimes. More than 5,700 lower-ranking personnel were charged with conventional war crimes in separate trials convened by Australia, China, France, The Netherlands, the Philippines, the United Kingdom and the United States. The charges covered a wide range of crimes including prisoner abuse, rape, sexual slavery, torture, ill-treatment of labourers, execution without trial and inhumane medical experiments. China held 13 tribunals, resulting in 504 convictions and 149 executions.

The Japanese Emperor Hirohito and all members of the imperial family, such as career officer Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, were not prosecuted for involvement in any of the three categories of crimes. Herbert Bix explained, "the Truman administrationand General MacArthur both believed the occupation reforms would be implemented smoothly if they used Hirohito to legitimise their changes".[2] As many as 50 suspects, such as Nobusuke Kishi, who later became Prime Minister, and Yoshisuke Aikawa, head of Nissan, were charged but released in 1947 and 1948. Shiro Ishii received immunity in exchange for data gathered from his experiments on live prisoners. The lone dissenting judge arguing to exonerate all arrested suspects was Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal.

The tribunal was adjourned on November 12, 1948.

Contents

[hide]Background[edit]

The Tribunal was established to implement the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Declaration, the Instrument of Surrender, and the Moscow Conference. The Potsdam Declaration had called for trials and purges of those who had "deceived and misled" the Japanese people into war. However, there was major disagreement, both among the Allies and within their administrations, about whom to try and how to try them. Despite the lack of consensus, General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, decided to initiate arrests. On September 11, a week after the surrender, he ordered the arrest of 39 suspects—most of them members of General Hideki Tōjō's war cabinet. Tōjō tried to commit suicide, but was resuscitated with the help of U.S. doctors.

Creation of the court[edit]

On January 19, 1946, MacArthur issued a special proclamation ordering the establishment of an International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). On the same day, he also approved the Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (CIMTFE), which prescribed how it was to be formed, the crimes that it was to consider, and how the tribunal was to function. The charter generally followed the model set by the Nuremberg Trials. On April 25, in accordance with the provisions of Article 7 of the CIMTFE, the original Rules of Procedure of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East with amendments were promulgated.[3][4][5]

Tokyo War Crimes Trial[edit]

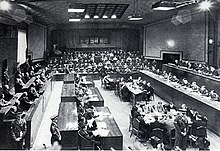

Following months of preparation, the IMTFE convened on April 29, 1946. The trials were held in the War Ministry office in Tokyo.

On May 3 the prosecution opened its case, charging the defendants with conventional war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity. The trial continued for more than two and a half years, hearing testimony from 419 witnesses and admitting 4,336 exhibits of evidence, including depositions and affidavits from 779 other individuals.

Charges[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Following the model used at the Nuremberg Trials in Germany, the Allies established three broad categories. "Class A" charges, alleging crimes against peace, were to be brought against Japan's top leaders who had planned and directed the war. Class B and C charges, which could be leveled at Japanese of any rank, covered conventional war crimes and crimes against humanity, respectively. Unlike the Nuremberg Trials, the charge of crimes against peace was a prerequisite to prosecution—only those individuals whose crimes included crimes against peace could be prosecuted by the Tribunal.

The indictment accused the defendants of promoting a scheme of conquest that "contemplated and carried out...murdering, maiming and ill-treating prisoners of war(and) civilian internees...forcing them to labor under inhumane conditions...plundering public and private property, wantonly destroying cities, towns and villagesbeyond any justification of military necessity; (perpetrating) mass murder, rape, pillage, brigandage, torture and other barbaric cruelties upon the helpless civilianpopulation of the over-run countries."

Keenan issued a press statement along with the indictment: "War and treaty-breakers should be stripped of the glamour of national heroes and exposed as what they really are—plain, ordinary murderers".

Comments

Post a Comment